Implementing Algorand Agreement

By: Eric deRegt and Nick Greenquist

Introduction

Bitcoin suffers from several technical problems. It is wasteful with significant energy usage and high fees. There is a high concentration of power as a few mining pools control the flow of money. The miners have low margins and are in known locations, which makes them susceptible to corruption. The ledger has ambiguity because of the possibility of forks as demonstrated by the emergence of Bitcoin Cash. There are real issues with scalability. It is unclear how the system will scale if millions of users are added to the system. Finally, there is a long latency because you have to wait a number of blocks before you can feel confident that your transaction is permanent.

In Algorand 1, there is a single blockchain. There are no forks or proof of work. This is achieved by the Algorand Agreement protocol, which guarantees agreement and consistency. There are several advantages to Algorand’s approach. The set of possible commands is smaller than Bitcoin which speeds up computation. There is true decentralization as no set of users has exogenous power. Payments are final because the probability of a fork is 1/10^-18. Scalability is bounded by the network latency. Finally, security is achieved against adversaries under extreme conditions.

Algorand selects random users known to the entire world. These users are in charge of proposing the next block and propagate the transactions to a small and random committee. The committee members are selected through a lottery where each member votes for himself. This leads to really fast selections that are random.

GitHub Link

The code for Algorand can be found here: Algorand

Algorand Overview

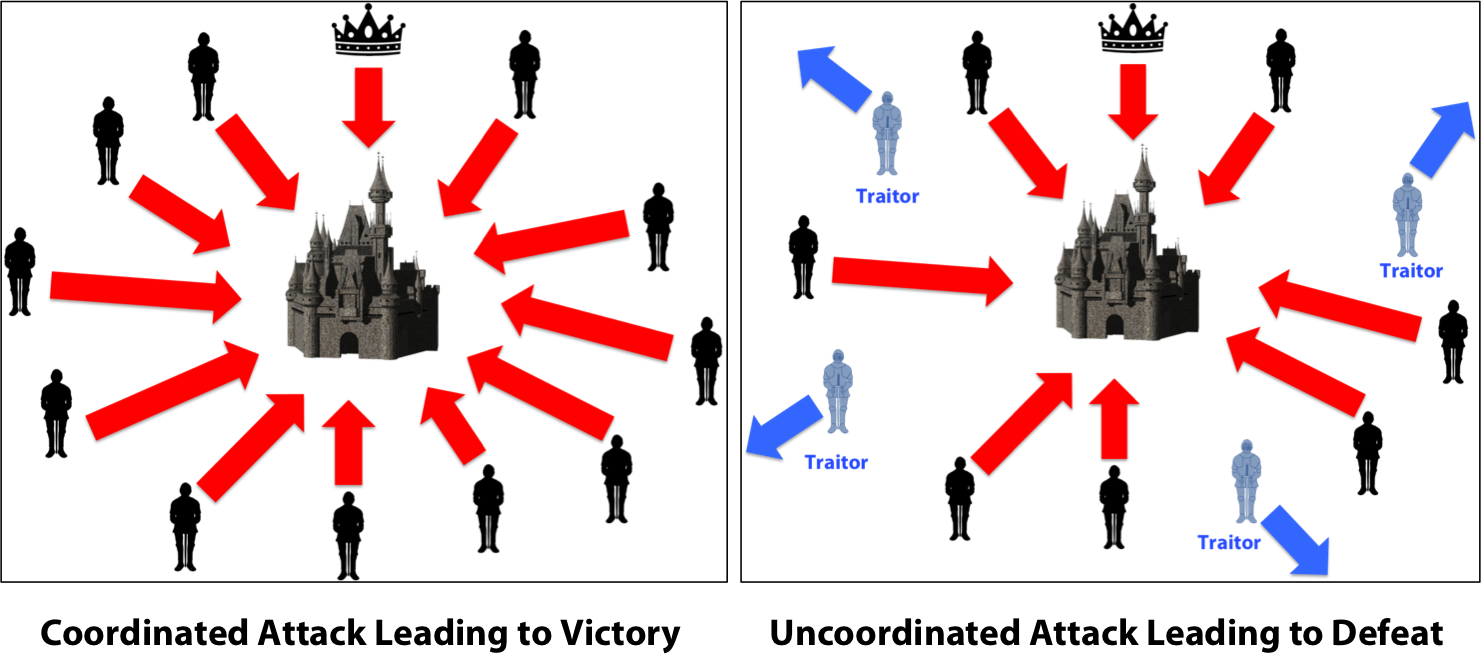

Algorand 1 is a cryptocurrency designed to scale to millions of users and confirm transactions in under a minute. Algorand seeks to overcome several challenges: preventing Sybil attacks, scaling to millions of users, and being resilient to denial-of-service attacks and other actions from an adversary that can coordinate with Byzantine nodes. Sybil attacks are combated by giving each user a weight based on their monetary stake in the protocol. If more than ⅔ of the stake is controlled by honest users, Algorand will reach consensus while avoiding forks and double-spending. The protocol produces scalability by the selection of the committee. Rather than every node participating in consensus, a small number of nodes are selected at random. To avoid attacks on committee members are selected privately through sortition and membership changes between rounds and steps.

Each user in the system has a public and private key. A transaction is a payment from one user to another and involves a user signing the message with its private key. As in Bitcoin, these transactions are broadcast to peers through a gossip protocol. Each users picks a small random set of peers to propagate messages to. Upon receiving a message, a peer will check the provided signature is valid before gossiping the message to other users. These transactions are put into a log which form the basis for new blocks. Each user takes these transactions and prepares a block in case they are chosen for block proposal.

Algrorand operates in asynchronous rounds and each round produces a new block which is appended to the blockchain. Each round users are selected to propose blocks and for a committee to reach consensus. These selections are made using an algorithm called cryptographic sortition. Soritition chooses a random set of users based on their weighted stake in the system. Verifiable random functions (VRF) are used to achieve this randomness. VRF takes a public seed and the role (proposer, committee member, etc.) for the sortition and returns a hash and proof. Selected users propagate the return values to peers through the gossip protocol. Other users can use public keys to verify that the hash and proof correspond to a given user. An initial seed is provided to all users and a new one is calculated for subsequent rounds by proposers during the agreement protocol. Since users are selected according to their stakes, a user with a high stake may be chosen multiple times in a given round or step.

Sortition is set above a certain threshold to guarantee with high probability that there will be greater than 1 proposer in each round. Since a block can be very large, users gossip two types of messages - one with just their priority and proof and one with the block. Users will select the highest priority proposer as their leader for the current round.

Algorand originally reached consensus using an algorithm called BA. In the first phase of BA, users reduce block agreement to two options. In the second phase, users agree on a propose block or agree on an empty block. Both of the phases have several steps, where committee members vote for a value and the other users count those votes. BA* completes the first phase in two steps. The second phase is completed in two steps if the proposer is honest and 11 steps with a malicious proposer. It is unclear if BA* was successfully implemented by the authors, but after some time another paper was released [2], which introduced a new consensus algorithm called Algorand Agreement. We are not sure what other changes were made to the protocol in the time since the release of the original Algorand paper, but we chose to use Algorand Agreement in our implementation.

Algorand Agreement Overview

Algorand Agreement 2 is a Byzantine agreement protocol that uses leader election and can operate in a partitioned environment. The protocol uses a hash function and digital signature (SIG), which returns the user id, message, and signed message. The signatures are unique for each public and private key pair.

There are a few assumptions for Algorand Agreement. Adversaries can coordinate optimally, but they cannot break the hash function or forge signatures. The set of all players is N, the cardinality of N is n = 3t + 1, and the number of malicious players is t. All players have access to a public random string R, which has been selected randomly and independently of the players’ public keys.

Agreement Protocol

Two communication settings are considered in the paper. In the first, nodes communicate over a synchronous network. Honest users send messages that are received by all other honest users within a given step. All messages seen by a user i before the start of a step are seen by all honest users at the end of the step because i will propagate all messages she has seen. In the second setting, nodes communicate through a propagation network. Nodes have timers with the same speed. The network can be arbitrarily partitioned and the adversary has full control during this time period. Messages are received by honest users within a known time whenever the network is not partitioned. We focused on the second communication setting for our implementation.

There are three types of messages that are sent in the protocol: next votes, soft votes, and cert votes. Additionally, users will send their credential (SIG(R, p)). If multiple nodes propose a block for a given round, a leader is chosen by iterating over SIG(R, p) and choosing the hash with the smallest value among valid participants.

There are five steps in each period p that run sequentially, described as follows.

Communication Setting 2: Steps

Step 1 is Value Proposal, which starts at time 0. Committee members propagate their block value and credential if its the first period or if they have received 2t + 1 next-votes for null in period p - 1. If they have received 2t + 1 next-votes for a value that is not null in p - 1, they propagate that value along with their credential for period p.

Step 2 is called the Filtering Step and takes place at time 2ƛ. In this step, a user i identifies his leader from all nodes that have propagated values and that are verified for that round. If the user has received 2t + 1 next-votes for null in p - 1, he will soft-vote his leader’s proposed value. If he has received 2t + 1 next-votes in p -1 for a value that is not null then he will soft-vote that value.

Step 3 is the Certifying Step and runs for clock times 2ƛ-4ƛ. If a user sees 2t + 1 non-null soft-votes for v that user cert-votes v.

Step 4 is the First Finishing Step at time 4ƛ. If a user has certified a value for period p, she next-votes v. If she has seen 2t + 1 next-votes for null in period p - 1, she next-votes null. Otherwise, she next-votes her starting value.

Step 5, which users enter after 4ƛ, is the Second FInishing Step, which she stays in until she can finish the period. If she sees 2t + 1 soft-votes for a non-null value, she will next-vote that value. If she sees 2t + 1 next-votes for null in p - 1 and has not certified in p, then she next-votes null.

These periods continue until the Halting Condition is reached. The Halting Condition is checked any time a cert-vote is received or cast. If a user sees 2t + 1 cert-votes for a value v, they append that value to their blockchain and move to the next round. These cert-votes can be from any period as nodes cannot ever change what value they will cert-vote once casting this type of vote.

Implementation

Our goal for the project was to create a working implementation of Algorand based on algorithms described in the Algorand1 and Agreement2 papers. We used the details from the Algorand1 paper to construct our overall structure and our algorithms for sortition, gossiping, and block proposal. We used Algorand Agreement2 for consensus and used Communication Setting 2 as described above.

Assumptions

We made a number of assumptions. Honest nodes are required to have at least 2t + 1 stake in the system. Nodes cannot lie about their userId or spoof messages. Nodes cannot change the result of sortition or verifySort. Timers are not synched, but they move at the same speed. Our sortition always selects two users, instead of implementing a probabilistic function with a targeted number of selected users. All users use the same sha256 hash function when using blocks and signatures. Every RPC message makes it to honest users. There are no retries for votes or propagate block messages.

Architecture

We organized our project in a similar manner to Lab 2: Raft. Each server runs identical code found in serve.go. Each node also initiates itself using the code in main.go. This code is responsible for gathering all the peers in the system, generating the node’s genesis block, connecting each server to their respective bcStore, and then starting the server.

bcStore stores the blockchain and serves as the connection between the server, client, and the blockchain itself.

In order to simulate a ‘user’ adding transactions to the blockchain, we seperated the ‘add transaction’ request functionality to client code. The client has a one-to-one relationship with a single server. The client can send transaction requests to a server through it’s port, and also get the current blockchain back by another request.

In addition to the main client, server, and bcStore relationship, there are a few other files that help keep the logic organized. All of the code for handling the 5 steps and the halting condition is found in agreement.go. All helper functions such as preparing block objects, hashing values, signing messages, creating SIG structs, generating the committee from sortition, verifying sortition, selecting the minimum leader hash, and initializing initial stake, are all stored in utils.go.

Details

All nodes who join the network create a bcStore which keeps a channel of commands they receive from clients and a blockchain data structure composed of blocks. Nodes connect to other known peers. The Algorand server runs on a goroutine and listens for several types of messages that can trigger different parts of the protocol and sends messages to other nodes.

Nodes keep track of several pieces of internal state. Each node keeps track of its private and public keys, what round, period, and step they are in, and their temporary and proposed blocks. Additionally, there is state for the periods in the agreement protocol. PeriodState includes values that have been proposed and who proposed them and all of the next-votes, cert-votes, and soft-votes used in agreement. We keep one state object for the current period and one for the previous period so that we can monitor the number of votes and appropriately terminate the agreement protocol when it is safe to add a block to our blockchain.

There are four RPC calls in our implementation - AppendTransaction, ProposeBlock, Vote, and RequestBlockChain. In order to pass messages between nodes using the four RPCs, we needed to create channels for both the RPC arguments and responses.

AppendTransactions are handled easily, where nodes simply return true to the broadcaster. Nodes also immediately respond true to the client after receiving a request to add a transaction. We left the client responsible to retry transactions if they later see that their requests did not make it into the updated blockchain. To enable this, clients can send a GET command to their server to receive the server’s current blockchain.

For ProposeBlock RPC, we also set up a channel to listen for any ProposeBlock messages. Whenever a message is received, the receiver first checks if the sender is approved for this round by calling verifySort. If the sender is approved, the receiver adds the proposed value and block to the their internal state that maps proposer credentials to their proposed value. Nodes always return true as long as they receive this message.

Handling incoming Vote messages requires a bit more logic. On top of extracting the correct type, nodes have to update their PeriodState with vote counts for specific values after checking that a sender has not already voted for that period.

RequestBlockChain requests are handled by simply passing the entire BlockChain into the response channel. The requester will then verify the returned blockchains in the response channel listener in order to decide if they need to replace their blockchain and update their current round and state.

In between rounds, each user keeps track of a TemporaryBlock, which they will use if selected for the committee. When a node receives a transaction from a client, it propagates that transaction to all other nodes through AppendTransaction. The nodes that receive these messages will add these transactions to their respective TemporaryBlocks. When we enter a new round, a proposer will compare the last block in their blockchain with their proposed block and remove any duplicate transactions before proposing a new block.

We created two timers to deal with separate problems: a RoundTimer and an AgreementTimer. The RoundTimer signals when users should enter into the first step of the agreement protocol for the next round. At this point, users will check if they have been selected by sortition to propose a block, and if so, they generate their credentials and broadcast a ProposeBlock message. ProposeBlock takes a block, credential, value, round, and peer as input and is sent to all peers. The value in this message is simply the hash of the block’s object byte memory.

The AgreementTimer signals when users should proceed between steps. It will first go off at the beginning of step 2. At each step we call a step function, which takes in the current PeriodState, last PeriodState, and required number of votes. The return value is either a value to propagate as Vote message, or a null value which is not acted on. Vote values are propagated using the Vote RPC. Vote takes the type of vote, round, and period as inputs and returns a boolean for success. Our Vote channel updates our vote state for the current and last period, keeping track of who has voted for what at each round and period. In the cert-vote branch, we also check for the halting condition. If we reach the halting condition, agreement has been reached and the block is appended to the node’s blockchain and the state is updated for the next round.

The final thing we considered was how to catch users up to new blocks. When a user receives a block proposal or vote, they can check if the sender is in a later round. If they are, the node may be in a state that is not up to date. This could occur if a node joins the network after it initially starts or if it fails and comes back online. In this case, the node will call the RequestBlockChain RPC to start the process of catching up to the current block so that they can rejoin the consensus process. Upon receiving a RequestBlockChainChan message, a node will respond by sending the current version of its blockchain. The node that is behind checks for the longest blockchain they have seen and verifies that the all blocks are valid by using verifySort on each block’s stamped credential.

Tradeoffs

We made a number of design decisions in our implementation that were required due to nonexistent or vague details in the papers. For the design decisions that were not described in great detail in the papers, we tried our best to look at other blockchains and come to a reasonable decision. A couple examples of this were introducing the round timer to kickstart agreement and adding the process for nodes to the catch up to the current round if they see they are behind.

We also had to simplify a couple parts of the system to narrow the scope of our implementation. The first area we simplified was the use of VRFs. Instead of using VRF for sortition, we used the round as a public seed and used a shuffle function we wrote to select users. Each user selects the same random index from a sorted list of userId’s using the same random seed to ensure equal committees across all nodes. We also didn’t use VRF for verifySort. Instead we used the same committee selection algorithm to verify the users had been selected. We assumed that stake does not change, but that it is randomly set at the beginning using peerId as seed. Two users are always selected by sortition for the block proposal stage. Finally, in our proposal we planned on implementing smart contracts on top of Algorand. We didn’t have enough time to implement smart contracts.

Challenges

There were several challenges we faced. Most were the result of the paper leaving out many implementation details.

Our biggest challenge was dealing with new users. We define new users as nodes that decided to join the network late or nodes that had recovered after failing. We decided that a new node should request the blockchain if they find out they are behind on the current round. This is easy to check as we send the round with each ProposeBlock and Vote message. We implemented a correct feature where users request, collect, and verify blockchains if they discover they are behind the current round. However, the real difficulty was getting the user to collect all ProposeBlock and Vote messages they missed out on, and also catch up to the correct period and step as the rest of the honest nodes.

Another challenge was in trying to implement VRF. It quickly became clear that it was not feasible to implement this function on our own. There were a number of cryptographic primitives that we were not well versed in and we didn’t feel we had enough time to implement a robust version of this algorithm. We looked at using the LibSodium C library used by the Algorand team, but ran out of time.

The original paper used a different agreement algorithm called BA*. We had spent some time understanding and working through implementation ideas for this protocol before learning that the Algorand team had released a new Algorant Agreement protocol. We decided that it made sense to use the newer protocol. However, it took us a while to understand the new algorithm and how to connect it to the main paper.

Testing

We tested our implementation in several ways. Initially, we started off by just trying to get a blockchain that sent transactions to peers, gathered blocks, and added blocks to the blockchain without any consensus mechanism. After this, we implemented Algorand Agreement and tested our implementation on four nodes manually using a client package similar to the one from Lab 2. We then ported the launch tool from Lab 2 and used this to test the system on a greater number of nodes with more transactions and allowing for node failures.

Correctness was tested using multiple nodes running at the same time. We sent transactions on different threads to multiple nodes that were running the Algorand server. We checked that the blockchain contained the same blocks after several rounds of the protocol. Blocks were analyzed to make sure hashes and transactions matched across nodes. Additionally, we tested with Byzantine behaviour by making certain peers always behave in a certain way. For example, with 4 nodes, we set peer0 to always propose their own block, only vote for their own values, and ignore all incoming messages from other nodes. The protocol was able to continue safely with the remaining 3 nodes despite peer0 trying to cause mayhem.

Liveness was another goal we tested for. We found that as long as 2t + 1 nodes are up at all times, Agreement rounds terminate eventually.

Performance was found to be very fast. Although we did not have the chance to test our implementation on hundreds of thousands of nodes like the authors of the Algorand paper did, we found that Agreement consistently completed very fast even when testing on Kubernetes using the launch tool with a few dozen nodes.

Conclusion

Algorand promises an extremely fast consensus protocol that would allow for a massively scalable and partition resilient cryptocurrency. Through implementing Algorand Agreement2, we were pleasantly surprised to find that the basic protocol is correct in a stable and small network of peers. However, the Algorand papers are severely lacking in numerous implementation details that are needed for even a minimum viable product with Algorand. The authors of the Algorand papers promise to make the Algorand code open source. However, only the VRF function has been released as of today. We hope the authors release more of the code in the future and uncover the missing pieces needed to make Algorand practical and useful in real use cases.

References

-

Yossi Gilad, Rotem Hemo, Silvio Micali, Georgios Vlachos, Nickolai Zeldovich. Algorand: Scaling Byzantine Agreements for Cryptocurrenices, https://people.csail.mit.edu/nickolai/papers/gilad-algorand-eprint.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Jing Chen, Sergey Gorbunov, Silvio Micali, Georgios Vlachos. Algorand Agreement: Super Fast and Partition Resilient Byzantine Agreement, https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/377.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4